This essay is adapted from an excerpt from an article that appeared in Jewish Action magazine by Dr. Jeanne Abrams

While early Denver was geographically far removed from the more established east coast Jewish communities, Colorado was also the site of growing observant Jewish community by the last decades of the nineteenth century, a number who arrived in the city from the failed Russian Jewish agricultural colony in Cotopaxi, Colorado, which had been unsuccessfully farmed by a group of sixty-three Orthodox Jews. Denver’s west side, comprised mostly of east European immigrants, soon became a traditionally Jewish enclave filled with numerous small shuls, kosher bakeries, and butcher and grocery stores. Other observant Jews migrated to Colorado in search of health as by the turn of the century Colorado had acquired a reputation as the “World’s Sanatorium” for those searching for a cure for tuberculosis or for the economic opportunities it offered to hardworking immigrants at the time.

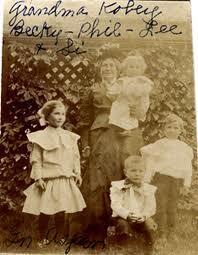

Courtesy University Libraries, University of Denver.

In the 1880s, Miriam Kubeski, or Mary Kobey as she was also known in America, and her husband Samuel Abraham and their children migrated from England to the mining town of Central City, Colorado, a silver boom mining town about thirty miles west of Denver. Miriam Rachofsky had been born in Suwalk, Poland, where her parents operated a small farm. At the age of 16 she was married to Abraham Kobesky, who was studying for semicha (rabbinical degree), and three children, two girls and a boy, were born to the couple while they lived in Poland. Economic hardships and pogroms in their native homeland propelled the Kobey family to search for a better life in Manchester, England. Abraham found a position as a Hebrew teacher and rabbi, and Miriam, who gave birth to three more sons in Manchester, launched her career as a midwife, often earning as much as a pound for each delivery. While in England, Miriam’s eldest daughter Rachel had married a young Torah scholar from Poland, Isaac Shwayder.

Before long news came of Miriam’s uncle Alexander Rittmaster’s success in America in the rugged mountains of Colorado, and her brother Abraham Rachofsky migrated to the Golden Land to join his uncle. Soon Miriam’s brother, now a prosperous dry good merchant in Central City, sent for his sister and her family. In 1879, Isaac Shwayder traveled on ahead to Colorado, where he worked with his uncle by marriage as a peddler. Rachofsky had organized the daily prayer services in a storefront in the mining town and had even acquired a Torah scroll, and the pious Isaac served as the unofficial rabbi in Central City for a number of years, although a synagoguewas never built.

Isaac was not reunited with his wife and children for two years. Family lore relates during that period he had once received a rare letter from his loved ones back in England on the Sabbath yet was still able to restrain himself from opening it until after sundown, so as not to desecrate the holiness of the day The extended family was overjoyed to finally join Isaac in Central City, but the absence of a real Jewish community in the mining camp was a disappointment for Miriam and her husband, as well as their daughter Rachel. The Kobeys actually became temporary vegetarians until they moved to Denver because kosher meat shipped from the larger town often arrived spoiled.

Once they relocated to Denver in 1888, Miriam, although now up in years, became a popular and respected midwife in the Queen City, and her husband Abraham was a founder of the Agudas Achim shul and earned a modest living as a rabbi and sofer (Torah scribe). In 1901 when the ordered matzahs from the Manischevitz Company failed to arrive, Rabbi Kobey and the local Jewish blacksmith stepped in and constructed an enormous oven at the back of the shul, where Rabbi Kobey and the shamus supervised the baking of matzahs for the entire community. In her charming memoir, The Tale of a Little Trunk, Miriam’s granddaughter later recalled Sabbath visits to the Kobey household, where her grandparents Miriam and Abraham would be “dressed in their Sabbath clothes in the sitting room, both engrossed in reading from the Torah. Grandma would be reading what was called the Teitch Hummish, a Yiddish version of the Bible, and Grandpa the Siddur or the Hebrew Bible.” The Jewish holidays were celebrated with special enthusiasm and Miriam would serve her family’s favorite dishes, kishka and tzimmis, in their small succah decorated with colorful ripe fruit and vegetables.

In her role as midwife, Miriam earned not only the occasional gold piece from wealthier clients but the nickname of Denver’s “Angel of Mercy” for her selfless concern for poor new mothers in the immigrant Jewish community. Indeed, acts of kindnessappears to have permeated her life. She volunteered her services at no charge to those who could not afford to pay and was frequently seen collecting money and clothing for baby layettes from merchants in the area and bringing her delicious homemade chicken soup to new mothers. Her granddaughter dubbed Mrs. Kobey “The Pied Piper of West Colfax,” the main street that ran through Denver’s east European immigrant enclave. She recalled that wherever Miriam Kobey went, wearing her trademark snow white cap over her hair, a spotless apron, and black bag prepared for a birth, she was trailed by a group of children, many of whom she had delivered, who affectionately regarded her as a surrogate grandmother.

Miriam Kobey was formally registered as a midwife in Denver’s city medical records, and her reputation spread far beyond the Jewish community. On one occasion Dr. Henry Buchtel, one of early Denver’s leading obstetricians, introduced her at a local medical convention as “the most famous midwife in Denver.” Mrs. Kobey passed away in 1921 leaving many descendants who would make a significant impact on the growth of Denver. Miriam and Abraham Kobey had been founders of Denver’s Jewish Free Loan Society, and the Shwayder name has been at the forefront of philanthropy in the Denver Jewish and general community for nearly a century.

Under Rachel’s influence, in the late 1880s the Shwayder family also moved to Denver so that their children could be part of the growing Jewish community, and as her granddaughter noted, Rachel Shwayder was the real “boss” in the family, a strong- minded matriarch who guided the household. Isaac opened a small grocery store, and like so many immigrant women, Rachel supplemented the family’s modest income by taking in boarders. Isaac and Rachel Kobey Shwayder’s sons would later found the Denver Shwayder Trunk Factory in 1910 which evolved into the world famous Samsonite Luggage Corporation.

Their daughter Hannah Shwayder Berry recalled Passover at her own parents table surrounded by the ten Shwayder children in early Denver, where to usher in the holiday, “Mama, her face all flushed from the heat of the kitchen, lighted the candles, covered her eyes with her hands, and chanted the ancient blessing.” In preparation for the family seder, Mrs. Shwayder brought out her Passover dishes and pots and spent days preparing the traditional foods on her blue enamel stove, such as gefilte fish (the hand ground product of a feisty carp which had been swimming in a large tub in the family’s backyard for several days), matzah knaidlach, borscht, and hand-grated horseradish.

Throughout the American West Jewish women like Miriam Kobey and Rachel Shwayder were instrumental in ensuring Jewish continuity. For example, the wives of Jewish farmers in Republic, Washington, at the turn of the twentieth century lived hard lives, with women out of necessity papering the walls of their wood cabins with newspapers to keep out the cold and carrying water to their houses from the nearby creek for cooking. Yet, Jenny Krajewski Shafran, the daughter of one of the farm families, recalled that “we observed all the Jewish holidays. I have never seen a more beautiful Pesach conducted to this day than in our little log cabin four miles from any neighbor, right in the middle of the woods.” Jews encountered unprecedented opportunities and acceptance in the fluid social order of the early highly multicultural American West and could have chosen to simply melt into the larger society and leave their traditional observances and customs behind. However, as the above stories demonstrates, a significant number of early Jewish settlers to the region met the new challenges and were successful in transplanting traditional Judaism to the western frontier, and Jewish women played a central role in the process.